Leap Year Secrets: 5 Shocking Facts You Didn’t Know

Every four years, February gets an extra day—February 29—thanks to the leap year. But why does this mysterious day exist? It’s not just a calendar quirk; it’s a vital fix keeping our time in sync with Earth’s orbit. Let’s dive into the science, history, and surprising traditions behind this fascinating phenomenon.

What Is a Leap Year and Why Does It Exist?

The concept of a leap year might seem like a minor calendar adjustment, but it plays a crucial role in maintaining the harmony between our human-made calendars and the natural rhythms of Earth’s journey around the Sun. Without leap years, our seasons would slowly drift, eventually causing summer to fall in December in the Northern Hemisphere. So, what exactly is a leap year, and why is it so essential?

The Astronomical Reason Behind Leap Years

Earth doesn’t take exactly 365 days to orbit the Sun. In fact, it takes approximately 365.2422 days—a little over 365 days and nearly 6 hours. That extra 0.2422 of a day may seem small, but over time, it accumulates. After four years, those extra hours add up to nearly one full day (4 × 0.2422 = 0.9688 days). To compensate, we add an extra day every four years, creating what we call a leap year.

This adjustment ensures that our calendar year stays aligned with the astronomical or tropical year—the time it takes for Earth to complete one full orbit around the Sun. Without this correction, the calendar would drift by about one day every four years. In just a century, that would result in a shift of roughly 24 days, meaning that spring would start in early April instead of late March.

- Earth’s orbital period: 365.2422 days

- Extra time per year: ~5 hours, 48 minutes, 46 seconds

- Accumulated every 4 years: ~23 hours, 15 minutes, 4 seconds

“The leap year is a brilliant compromise between the precision of astronomy and the practicality of human calendars.” — Dr. Neil deGrasse Tyson

How Leap Years Keep Seasons on Track

One of the most important functions of the leap year is to stabilize the timing of the seasons. The vernal (spring) equinox, for example, is a key reference point in many calendars, including the Gregorian and Julian systems. If leap years were not implemented, the equinoxes and solstices would gradually shift earlier each year.

Imagine celebrating Christmas in the middle of summer in the Northern Hemisphere—this would eventually happen without leap year corrections. Ancient civilizations, such as the Egyptians and Romans, recognized the need for calendar reform to prevent such seasonal drift. The introduction of the leap year was a pivotal step in creating a more accurate and reliable calendar system.

Modern society relies on this alignment for agriculture, religious observances, and even economic planning. Farmers depend on predictable growing seasons, and holidays like Easter are calculated based on the spring equinox. Thus, the leap year isn’t just a quirky addition—it’s a cornerstone of temporal order.

The History of the Leap Year: From Roman Times to Today

The idea of adding extra days to the calendar isn’t a modern invention. Its roots stretch back over two millennia to ancient Rome, where early attempts to align the calendar with the solar year led to the birth of the leap year concept. Understanding its evolution reveals how human ingenuity has shaped the way we measure time.

Julius Caesar and the Julian Calendar

The first known implementation of a leap year system came in 45 BCE with the introduction of the Julian calendar by Julius Caesar. Advised by the Alexandrian astronomer Sosigenes, Caesar reformed the Roman calendar, which had become severely misaligned with the seasons due to inconsistent intercalation (the insertion of extra months).

The Julian calendar established a simple rule: a leap day would be added every four years without exception. This created an average year length of 365.25 days—very close to the actual solar year of 365.2422 days. While this was a massive improvement, the slight overestimation (by 0.0078 days per year) meant that the calendar would still drift over centuries.

Despite its imperfection, the Julian calendar was a revolutionary step forward. It was used throughout Europe for over 1,600 years and laid the foundation for future calendar reforms. You can learn more about the Julian calendar’s impact on history at Encyclopedia Britannica.

The Gregorian Reform of 1582

By the 16th century, the accumulated error from the Julian calendar had caused the vernal equinox to shift from March 21 to around March 11. This discrepancy posed a serious problem for the Catholic Church, which used the equinox to calculate the date of Easter. Pope Gregory XIII commissioned a reform to correct this drift, resulting in the creation of the Gregorian calendar.

The new system kept the leap year every four years but introduced an exception: years divisible by 100 are not leap years unless they are also divisible by 400. For example, 1700, 1800, and 1900 were not leap years, but 1600 and 2000 were. This adjustment reduced the average year length to 365.2425 days—extremely close to the tropical year.

The Gregorian calendar was initially adopted by Catholic countries, while Protestant and Orthodox nations resisted for decades or even centuries. Greece, the last European country, adopted it in 1923. Today, it is the most widely used civil calendar in the world. More details on the Gregorian reform can be found at Time and Date.

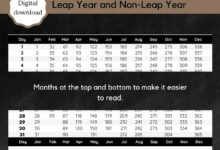

How to Determine a Leap Year: The Simple Rules

While the concept of a leap year might seem complex, the rules for identifying one are actually quite straightforward. Whether you’re checking a historical date or planning for the future, knowing how to determine if a year is a leap year is a useful skill. Here’s a clear breakdown of the algorithm used in the Gregorian calendar.

The Four-Step Leap Year Test

To determine if a given year is a leap year, follow these four simple steps:

- Is the year divisible by 4? If not, it is not a leap year.

- If yes, is it divisible by 100? If not, it is a leap year.

- If yes, is it divisible by 400? If yes, it is a leap year.

- If no, it is not a leap year.

Let’s apply this to a few examples:

- 2024: Divisible by 4? Yes. By 100? No → Leap year

- 1900: Divisible by 4? Yes. By 100? Yes. By 400? No → Not a leap year

- 2000: Divisible by 4? Yes. By 100? Yes. By 400? Yes → Leap year

- 2100: Will be divisible by 4 and 100, but not 400 → Not a leap year

This system ensures that the calendar remains accurate to within one day every 3,236 years—a remarkable feat of timekeeping precision.

Common Misconceptions About Leap Years

Despite the clear rules, several myths persist about leap years. One common misconception is that every four years is automatically a leap year. While this is mostly true, the century rule (divisible by 100 but not 400) creates exceptions that many people overlook.

Another myth is that leap seconds and leap years are related. In reality, leap seconds are added to account for irregularities in Earth’s rotation, while leap years correct for the orbital period around the Sun. They serve different purposes and are managed by different organizations.

Some also believe that leap years bring bad luck or unusual events. While cultural superstitions exist, there is no scientific evidence linking leap years to increased misfortune. In fact, many people born on February 29—known as “leaplings” or “leap year babies”—celebrate their uniqueness rather than fear it.

Leap Day Traditions and Cultural Celebrations

February 29, or Leap Day, is more than just a calendar anomaly—it’s a day rich with folklore, traditions, and unique celebrations around the world. From ancient customs to modern festivities, leap day has inspired everything from romantic role reversals to special legal rights.

Women Proposing to Men: The Irish Legend

One of the most famous leap year traditions originates in Ireland and dates back to the 5th century. According to legend, St. Bridget complained to St. Patrick that women had to wait too long for men to propose. In response, Patrick allegedly declared that women could propose to men on February 29 every four years.

This custom spread to Scotland and later to England and the United States. In some versions of the story, if a man refused a proposal on leap day, he was required to give the woman a gift—such as a silk gown, a kiss, or even money—as compensation. Today, this tradition is celebrated playfully, with some companies even offering “Leap Year Proposal Kits” for women.

While the historical accuracy of this tale is debated, it has become a beloved part of leap year folklore and is often cited as an early example of gender role reversal in courtship rituals.

Leap Year Babies: Life on February 29

Being born on February 29 is a rare occurrence, with odds estimated at about 1 in 1,461. These individuals, affectionately called “leaplings” or “leap year babies,” face unique challenges and joys. Legally, most countries allow them to celebrate their birthday on February 28 or March 1 in non-leap years.

Some leaplings choose to celebrate only on the actual leap day, making their birthday a once-every-four-years event. Others celebrate annually, treating the date as a flexible milestone. Notable leap year babies include rapper Ja Rule (born 1976), motivational speaker Tony Robbins (1960), and actress Dinah Shore (1916).

Organizations like the Honor Society of Leap Year Day Babies have formed to connect people born on February 29. They host events, share stories, and even campaign for official recognition of leap day as a special observance.

Scientific and Technological Impacts of Leap Years

Beyond cultural traditions, leap years have significant implications for science, technology, and global systems. From satellite operations to software programming, the extra day can introduce complexities that require careful planning and adjustment.

Timekeeping and Satellite Navigation

Global Positioning System (GPS) satellites rely on extremely precise atomic clocks to calculate positions on Earth. These systems must account for leap years to maintain synchronization with Earth’s rotation and orbit. While GPS time does not include leap seconds, the underlying calendar framework still depends on accurate leap year calculations.

Astronomical software, such as planetarium programs and orbital prediction models, must also incorporate leap year logic to ensure accurate simulations. Even a one-day error can result in significant miscalculations over long time spans, affecting everything from eclipse predictions to spacecraft trajectories.

Software Bugs and the Leap Year Problem

Leap years have been the source of numerous software glitches throughout history. In 1996, Microsoft Excel incorrectly treated 1900 as a leap year (it wasn’t), causing date calculation errors. This bug was retained for compatibility reasons and still exists in modern versions.

In 2012, a leap year bug caused some Android devices to crash or display incorrect dates. Similarly, in 2020, several websites and systems experienced issues due to improper handling of February 29. These incidents highlight the importance of robust date-handling algorithms in software development.

Programmers are advised to use standardized libraries (like Python’s datetime module or Java’s java.time) rather than writing custom date logic, which can introduce errors. The U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) provides guidelines for leap year compliance in critical systems. Learn more at NIST Time and Frequency Division.

Leap Years in Different Calendars Around the World

While the Gregorian calendar is the global standard for civil use, many cultures and religions follow alternative calendars that handle leap years differently. These systems reflect diverse astronomical observations, religious beliefs, and historical traditions.

The Hebrew Calendar and Its 19-Year Cycle

The Hebrew calendar is a lunisolar system, meaning it combines lunar months with solar years. To keep the months aligned with the seasons, an extra month—Adar I—is added seven times every 19 years. This 19-year cycle is known as the Metonic cycle.

For example, in a leap year on the Hebrew calendar, the month of Adar is doubled, with Purim celebrated in the second Adar (Adar II). This ensures that Passover always falls in the spring, as required by Jewish law. The next Hebrew leap year will be 5785 (2024–2025).

The Islamic Calendar and the Absence of Leap Years

Unlike the Gregorian and Hebrew systems, the Islamic calendar is purely lunar, consisting of 12 months based on the Moon’s phases. It has 354 or 355 days per year, which is about 11 days shorter than the solar year. As a result, Islamic months drift through the seasons over time.

There are no leap years in the traditional Islamic calendar, although some proposed reforms have suggested adding intercalary days. The lack of synchronization with the solar year means that Ramadan, for instance, can occur in any season depending on the year.

The Chinese Calendar and Intercalary Months

The traditional Chinese calendar is also lunisolar, with leap months added approximately every three years to keep the calendar in sync with the solar year. A leap month is inserted when a lunar month does not contain a “principal solar term,” one of 12 key points in the solar year.

For example, in 2023, a leap month (Leap February) was added, making it a 13-month year in the lunar cycle. This system ensures that festivals like Chinese New Year remain in their proper seasonal context.

Future of the Leap Year: Will It Last Forever?

As our understanding of astronomy and timekeeping evolves, the future of the leap year remains a topic of scientific discussion. While it has served humanity well for centuries, long-term changes in Earth’s rotation and orbit may require new solutions.

Earth’s Slowing Rotation and Its Effects

Earth’s rotation is gradually slowing due to tidal friction caused by the Moon. This means that the length of a day is increasing by about 1.7 milliseconds per century. Over millions of years, this could affect the accuracy of our calendar system.

In the distant future, the tropical year may no longer require a leap day every four years. However, this change is so gradual that it won’t impact the current leap year system for tens of thousands of years. For now, leap years remain a reliable solution.

Potential Calendar Reforms

Some scientists and calendar reformers have proposed alternative systems to eliminate the complexity of leap years. One such proposal is the International Fixed Calendar, which divides the year into 13 months of 28 days each, with one or two “Year Days” outside the regular week cycle.

Another idea is the World Calendar, which features a 364-day year with an extra “Worldsday” added at the end of the year (and another in leap years). These systems aim for perpetual alignment, where dates fall on the same weekday every year.

While these proposals offer simplicity, they face resistance due to religious, cultural, and logistical challenges. For the foreseeable future, the Gregorian leap year system is likely to remain in place.

Fun Facts and Trivia About Leap Years

Leap years are full of fascinating quirks and curiosities that go beyond science and tradition. From rare birthdays to pop culture references, here are some entertaining facts that highlight the uniqueness of February 29.

Rarity of Leap Day Births

The odds of being born on February 29 are approximately 1 in 1,461, making leaplings a rare group. Statistically, about 5 million people worldwide are estimated to have been born on this day. In the U.S., the National Center for Health Statistics estimates around 187,000 leap year babies.

Some hospitals have recorded unusual patterns on leap days, though no definitive “leap day baby boom” has been proven. Still, the day remains a point of interest for demographers and statisticians.

Leap Year in Pop Culture

Leap years have inspired movies, songs, and literature. The 2010 romantic comedy Leap Year, starring Amy Adams, centers on the Irish tradition of women proposing on February 29. While fictional, the film brought renewed attention to leap year customs.

The band Bowling for Soup released a song titled “1 in 1461,” referencing the odds of being born on leap day. Meanwhile, in literature, authors like James Joyce and Kurt Vonnegut have made subtle references to time anomalies, though not always directly to leap years.

“Time is an illusion. Leap year doubly so.” — Paraphrasing Einstein with a twist

Why do we have a leap year?

We have a leap year to keep our calendar in alignment with Earth’s orbit around the Sun. Since a solar year is about 365.2422 days long, adding an extra day every four years compensates for the extra fraction of a day, preventing seasonal drift.

Is every four years a leap year?

Mostly, but not always. While leap years occur every four years, years divisible by 100 are not leap years unless they are also divisible by 400. For example, 1900 was not a leap year, but 2000 was.

What happens if you’re born on February 29?

People born on February 29, known as leaplings, typically celebrate their birthdays on February 28 or March 1 in non-leap years. Legally, most countries recognize either date for official purposes like driver’s licenses and passports.

How often does a leap year occur?

A leap year occurs every four years, but with exceptions. Over a 400-year cycle, there are 97 leap years, making the average frequency about once every 4.1 years.

Will there ever be a leap year with two leap days?

No. There is no provision in the Gregorian calendar for adding more than one leap day. The system is designed to add exactly one day—February 29—every leap year to maintain accuracy.

The leap year is far more than a calendar oddity—it’s a testament to humanity’s quest to harmonize time with the cosmos. From ancient Roman reforms to modern satellite systems, the leap year bridges science, culture, and tradition. Whether you’re a leapling celebrating a rare birthday or simply curious about why February occasionally gets an extra day, understanding the leap year reveals the intricate dance between Earth and time. As long as our planet orbits the Sun, the leap year will remain a vital, fascinating part of how we measure our lives.

Further Reading: